Why would a veteran of the War of 1812 be unlisted in military records, left out of history journals, and omitted from monuments and plaques? Because the country in which he was born did not consider him to be a rights-holding citizen.

Columbia Center Cemetery in Columbia Township, Ohio, records show that Frederick Hart, who was buried there after his death on October 21st, 1864, served in of the War of 1812. His descendants knew his life story, and likely had his grave marker decorated with the service medallion, but very little detail of that story has been documented or preserved in other public records due to the practices of slavery and residual racism. Traces of his presence exist in narratives and inter-family connections and the resulting circumstantial evidence is bringing Hart’s story to the surface once again.

In 1808, Frederick Hart’s enslaver, Lexington businessman Colonel Thomas Hart, died suddenly. Col. Hart’s eldest son General Thomas Hart III died soon thereafter in 1809, leaving the second son Nathaniel Gray Smith Hart the rope walk and hemp warehouse businesses. The Harts utilized enslaved workers, hired out from their enslavers, to operate these facilities as well as a nail factory and forge and other enterprises. The 1810 census shows N. G. S. Hart with eighteen enslaved persons in his household, with one person of a similar age to Frederick. No records have been found to indicate where he resided or whether he had a wife or family during this time period. Despite the legal change of enslaver ownership, it is likely Frederick Hart remained in a day to day pattern of working in one of the Hart family enterprises, at least for a few years.

In August of 1812, N. G. S. Hart, a Fayette County Magistrate and an attorney who studied under his brother-in-law Henry Clay, called upon the volunteers of the Lexington Light Infantry to prepare to go to war. The volunteer militia of 90 men, sometimes referred to as the “Silk Stocking Boys”, was led by Captain N. G. S. Hart in a parade through Lexington as they headed to join the Northwest Army in Fort Wayne. The officers of this regiment were wealthy landowners and businessmen, and as they were accustomed to personal service, most brought a so-called “body man” along with them. Likely Capt. Hart brought Frederick Hart with him to assist in matters such as care of the horses, uniforms, meals, and logistics. Though these enslaved soldiers were not armed, their skills were relied upon for the support of the regiment.

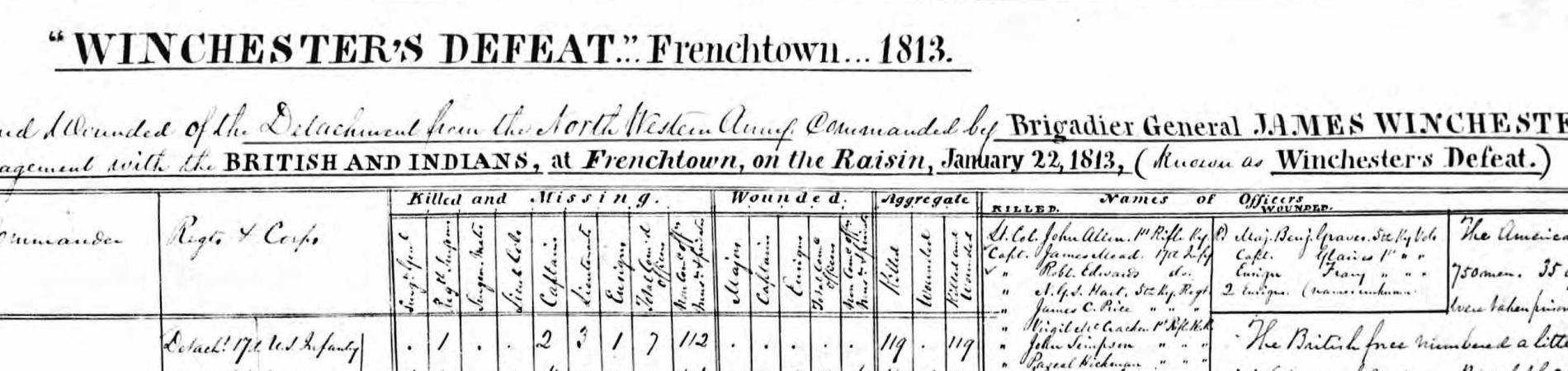

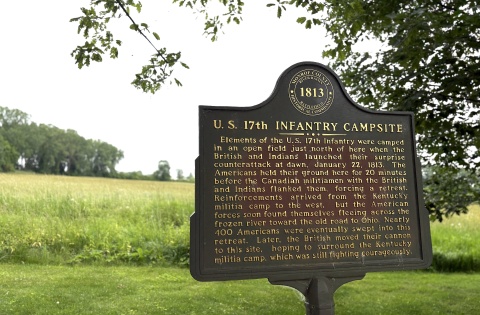

The Battle of Frenchtown, one of the bloodiest battles of the War of 1812, took place in January of 1813 in frozen winter conditions, along the River Raisin near the eastern edge of present day Michigan along Lake Erie. Capt. Hart was wounded on January 22nd, and taken along with other casualties to nearby homes in Frenchtown. The following day, as the wounded were being transported out of town on sleds, they were attacked by British-aligned Wyandot and Potawatomi in what would become known as the River Raisin Massacre. Capt. Hart and approximately 30-40 other wounded soldiers were scalped and killed [1]. General William Henry Harrison’s attempt to re-capture Detroit had failed and many Kentuckians were included in the hundreds of men killed and wounded during this battle, which also became known as the Battle of the River Raisin or Winchester’s Defeat. A noted survivor of the River Raisin Massacre is renowned portrait painter Matthew Harris Jouett, who painted portraits of Capt. Hart and members of the Hart, Brown, and Shelby families [2].

Though there is no official record of what happened to Frederick Hart during or after this battle, it is likely that he was included in the prisoners of war taken by British General Procter to Fort Malden in Canada. According to testimony within G. Grant Clift’s “Remember the Raisin” some of the African American prisoners of war who had been enslaved to officers were then forced to serve Potawatomi chiefs. In April of 1813, “Captain [Nathaniel] Hart’s servant at the same time was reported alive but his whereabouts uncertain”[3].

Potentially Frederick Hart made his way back to Kentucky to the Hart estate, where Capt. Hart’s widow, Anna Edwards Gist Hart, resided with two young sons, Thomas and infant Henry. It is unclear whether Frederick stayed at the estate during this time, working once again at the family businesses, or was perhaps rented out for labor elsewhere. When Anna Hart died young in 1818, it is unclear what happened to Frederick Hart next but inter-family connections may hold the answer. Capt. Hart’s sister Ann (Nancy) was married to former KY Secretary of State James Brown, brother of former Senator John Brown of Frankfort, KY. One of Hart’s other sisters, Lucretia, was married to Henry Clay of Lexington, an attorney and landowner with numerous enslaved people on his estate Ashland.

James Brown had been appointed in 1804 by President Jefferson as Secretary of the Territory of Orleans, and in the intervening years became one of the wealthiest landowners and enslavers on the German Coast. During the spring of 1813, James Brown was serving as Senator from Louisiana. It is unclear why Frederick Hart wound up at Liberty Hall in Frankfort, but it appears that he was inherited through the family connection with Nancy Brown. Perhaps Nancy moved back to Frankfort KY following the horrific violence in the aftermath of the slave rebellion in 1811, known as the German Coast Rebellion. If she were living with her husband’s family at Liberty Hall, Frederick Hart would have been a helpful addition to the house staff. In an 1822 letter to James Brown’s brother, Preston Brown, who was then residing at Liberty Hall, there is a mention of a man named Frederick who had been rented out to a Mr. Allen [4]. This is one of the only written clues of Fredrick’s presence in the Brown family at this time.

James and Nancy Brown did not have any children, and Nancy Hart died in 1830. James’ brother John (of Liberty Hall) administered his will in 1835. Around that same time, John Brown gave Liberty Hall to his eldest son Mason, and divided the four acres on which it sat between Mason and his younger son Orlando. Immediately following this inheritance, a grand home was designed and built for Orlando. Records of the construction of this home include details on the dimensions of the “Negro housing” at fifteen feet by seventeen feet by eight feet. Plasterer Henry “Harry” Mordecai’s invoice includes work for “Negro Houses” as well [5]. Was Frederick involved in the construction of this home? Was one of these houses built for him? Aerial maps show several structures behind the Orlando Brown house as well as along the alley behind Liberty Hall. There are a couple of photographs in the Liberty Hall collection showing these simple frame structures, but nothing physically remains of these buildings at the site today. When John Brown died in August of 1837, the remains of his estate went to his sons Mason and Orlando.

In 1841, Orlando Brown was the editor of the newspaper The Frankfort Commonwealth, where on June 1st he wrote the following:

“The first child born in Kentucky was born in Boonesborough and is now living in the family of the Editor of the Commonwealth. He is a yellow man, the child of a servant who came out as a cook for Co. Hart’s company. We expect to be at the Harrodsburg celebration, and Old Frederick will appear in the capacity of our carriage driver. On looking at him, so full of life and vigor as he is, one can scarcely realize the fact that he is the first born in a State so teeming with so many inhabitants as now fill the Dark and Bloody ground."

By 1842, Frederick Hart had been manumitted and was still living at the home of Orlando Brown, likely in one of the cottages behind the main Brown family home.

According to the “List of Free Negroes Taken by the Trustees of Frankfort July 16, 1842”[5.1] of which Orlando Brown was a trustee, the original document housed at the Filson Historical Society* listed Frederick Hart working as a farmer, with no property, aged 65, standing indicated with a “G”. In the transcription of this document labeled “Frankfort, KY Census of Free Blacks, 1842” in the National Genealogical Society Quarterly in 1975, the entry says “65, laborer, lives with O. Brown, character good”[6].

Thumbnail: Returns of the Killed and Wounded American Troops 1790 - 1840

About the Author:

Rachel Grimes is a composer and pianist based in Kentucky who creates music for chamber ensembles, orchestras, film, multi-media installations, and collaborative live performances. She is a multi-generational Kentuckian interested in how genealogy and history research can lead to social change. She has been a member of African-American Genealogy Group of Kentucky since 2019, and a Board member since 2024. She is a past Board member of the Port William Historical Society, and is a member of the Filson Historical Society, Madison County Historical Society, and the Fort Boonesborough Foundation. www.rachelgrimespiano.com

Sources and Further Reading:

[1] Lexington’s Light Infantry by John Trowbridge, Kentucky National Guard Historian

[2] Catalogue of All Known Paintings by Matthew Harris Jouett by Mrs. William H. Martin (1939)

[3] G. Grant Clift’s “Remember the Raisin” (1909)

[4] Attorney S. Q. Richardson to Preston Brown, 7/31/1822, Liberty Hall library

[5] Orlando Brown construction invoices; Letter James Harlan to Orlando Brown May 19th, 1850. Orlando Brown Papers. Filson Historical Society.

[5.1] List of Free Negroes Taken by the Trustees of Frankfort July 16, 1842. Orlando Brown Papers. Filson Historical Society.

[6] Frankfort, KY Census of Free Blacks, 1842 in the National Genealogical Society Quarterly (1975)

Amongst My Best Men: African Americans and the War of 1812 by Gerard T. Alton

A Hundred Years Ago “The River Raisin” by A. C. Quisenberry, The Register of the Kentucky Historical Society, September 1913

riverraisinbattlefield.org

Next: Part 4: Manumission to Self-Determination